In today’s climate of purchasing modern luxury timepieces, chances are, you’ve been a part of multiple conversations which had some common elements. Likely, someone has voiced their discontent about how the hobby has become unapproachable for “true” enthusiasts. Or perhaps, you’ve heard a friend or two ardently proclaim how they’ll “never pay more than retail [MSRP]” for a watch that they’re after or how a certain timepiece is “not worth a penny over list price.” Extend the list of grievances a little further and maybe you’ve heard mentions of dissatisfaction with extended wait times or how the price of certain watches [particularly on the grey market] keep going up. It isn’t unusual to come across someone noting that no matter how close one gets to saving for a particular watch, by the time they’ve amassed enough, the price of the watch has further increased. While I understand the premise of these convictions, I’m beginning to wonder… do these opinions really reflect a reasonable paradigm for what we expect of the contemporary watch buying process?

At first blush, these above-mentioned issues may seem like a list of different problems, but many are clearly interconnected. No doubt, the watch market has evolved substantially in the last few years and many things have changed, but I believe there are some basic economic principles that can help us make sense of what we’re seeing. To illustrate this point, I think as good a place to start as any is the concept of MSRP.

Let’s try to take a closer look at this benchmark. A common term, Manufacturer’s Suggested Retail Price is often referred to as “retail,” “list,” or “RRP”. Typical in the automotive, electronics, or appliance industries, it is what the manufacturer recommends as the price for the consumer at the final point of sale. To better understand this, we need to recognize that most watches [or similar goods with an MSRP] are not sold directly to the customer at or by the entity that makes it. There is at least one middleman involved. So within the watch retail space, there’s a different price that the middleman (usually an authorized dealer, wholesaler, jeweler, store etc…) pays the manufacturer than a customer pays for the watch. The recent expansion of the watch boutique model has changed this traditional product chain, but let’s temporarily leave that out of the equation. It’s important to realize that the MSRP reflects a suggestion to the retailer which incorporates a certain amount of profit, overhead, insurance, manpower, aftersales care and other costs of typically doing business with a customer. Obviously, unique markets, retail locations, and consumer demographics influence these factors in different ways. So the MSRP for a store in a prime retail district (like 5th ave NYC), vs one in low labor-cost zone, or a one in a low-tax district, or a retailer on the other side of the world from the manufacturer’s factory (think of varying shipping and transport costs) may all have different reasons to charge different amounts for the same item. Add to this the fact that different markets have different demands and quickly, we can surmise that the item’s costs will vary accordingly. While manufacturers tend to price things with some of these variables in mind, usually by assigning MSRP to a region (looking up most high end watches on-line will require the website to identify a geographic location), there is no formula for guaranteeing consistent profit margins across the board for all involved parties. Inherently, this makes MSRP a loose benchmark.

The concept of a “perfect market” and a “price taker” :

Without getting too much into economic theory, it’s important to touch upon some elementary concepts. First is that of a perfect market (sometimes referred to as a “perfectly competitive market”). This is a situation where, for a given product (or service), there is enough demand and supply without any underlying market manipulation. It is also assumed that buyers are well informed, monopolies do not exist and thus, the equilibrium between the supply of the product and its demand dictates the market price. This basically describes the forces that allow for grey market pricing, not MSRP. MSRP, especially in the context of in-demand watches made by manufacturers that have high brand cache, is set independently of the forces that govern a modern “perfect market” and thus can never accurately reflect the actual value of a product. This makes MSRP more of a theoretical value than a practical value.

A counter-argument to the above point is that companies such as Rolex and PP are indeed monopolies and supply is limited (and thus the perfect market conditions need not apply). This of course, suggests an imperfect market.

As an example, if a consumer wants to buy a desirable watch directly from an AD, expect to pay MSRP, and actually get the watch within some reasonable time frame (forget the years-long waitlists), then the consumer has to realize that they are expecting to pull together components of two completely different market models. It bears mentioning that waitlists for many of the very desirable watches (where people seem to be most interested in paying MSRP to begin with) project out to years, if not close to a decade. Over such a span of time, expecting the MSRP to stay static is illogical.

Certain things inherently go together:

In an imperfect competitive market, you have monopolies, price makers, exclusive or luxury items, non-traditional supply/demand curves (think Veblen goods), long wait times, opacity in pricing and thus: an MSRP that is based on non-transparent factors (price is determined by what the manufacturer deems to be an appropriate price, not just straightforward supply and demand forces) .

By contrast, in the perfect competitive market, you do not have price makers, but rather price takers (this includes the manufacturer!), traditional supply/demand curves, transparency (everyone can see manufacturing costs and what others are paying/charging), and a price that is determined by the conglomerate of market factors (and not individually by buyers, sellers, manufacturers, or any other vested parties). The product is also available to the buyer at the time that they are ready to pay market price.

So what is it worth?

This brings up the question of how the value of a watch is determined. To be clear, this is quite possibly the murkiest part of the equation, and by “value,” I do not mean only the price. One can argue that for a Veblen good (as the price rises, the demand goes up), the intangible factors play a huge role in value determination (which, in turn, determines price and subsequently, demand). How scarce a product is, how it affects one’s social status to own it, and any “investment potential” for long term value gain are all examples of intangible value adders that cannot be quantified by just price alone. It is also worth briefly mentioning that happiness derived from ownership is typically not a perceived added value in these situations. But I digress.

In any case, these added intangible values become less a component of basic market parameters inherent to supply and demand (typically seen in “perfect market” scenario) rather than to subjective, perceived, or implied components that advertising and marketing try to capitalize upon (“imperfect market” conditions).

Now technically, no market is perfect. But a consumer cannot expect to pick and choose characteristics of the purchasing process from both categories. Let’s say someone decides that they “won’t pay a dime over retail” for an exclusive watch. It goes without saying that this consumer also has to expect that they will experience delivery latency, may never receive the item they want to purchase, and cannot expect past market forces to dictate future pricing trends (complain about how things “used to be before the hype.”) If one wanted to purchase a watch before it became very desirable (essentially, the item switched from a perfect market condition to an imperfect market condition), that buyer unfortunately missed out. The watch is not an essential commodity, and thus cannot be expected to be regulated in the same manner as food, clothing, fuel, etc… Also, if one expects to get a watch at retail price in an imperfect market, the market will require you to compensate the gap (between MSRP and grey market price) in a different way.

Minding the gap:

Examples of manufacturers which are distancing themselves from MSRPs they’ve utilized in the past include market players like AP, FP Journe and PP.

In today’s economy, the scenario where second-hand prices for some goods are much higher than the purchase price of the same item (when bought new) is becoming more commonplace. I’ve often wondered if it helps manufacturers to increase their MSRPs to that which is being charged by the grey market. Due to a variety of reasons, I believe that it does not.

For one, a higher second-hand market price than an MSRP is a key ingredient in building desirability for a brand. Of course other inter-related components govern this price equation — low supply, high demand, as well as branding that reflects exclusivity and status. However, once the threshold of MSRP has been consistently and substantially crossed by the grey market price, the brand (often referred to as “the firm” in economic terms) has gone from being a price taker (a dependent position) to a price maker (a favorable and rather lucrative position). Further, the difference (gap) between the MSRP and second-hand market price also represents some measurable quantification of value added to an item that cannot be delineated by just its MSRP alone. These are the previously referred to “intangible value adders.” They represent such things as social status, scarcity, or “investment potential” to name a few.

As a thought experiment, I imagined a marketing strategy where a manufacturer could actually lower MSRP as grey market prices increased (it would never actually happen because there’s just too much money being left on the table). In this hypothetical example, the “gap” between MSRP and retail would increase further, thereby portraying an increased desirability of the watch. As unusual as it sounds, if a watch is worth 10X retail as opposed to 2X retail, it almost doesn’t matter what the actual MSRP is. It matters more what the multiplier to obtain it on the grey market is. And this important for to driving brand image and desirability when it comes to luxury goods that are basically non-utilitarian material objects.

Six in one hand, 1/2 dozen in the other:

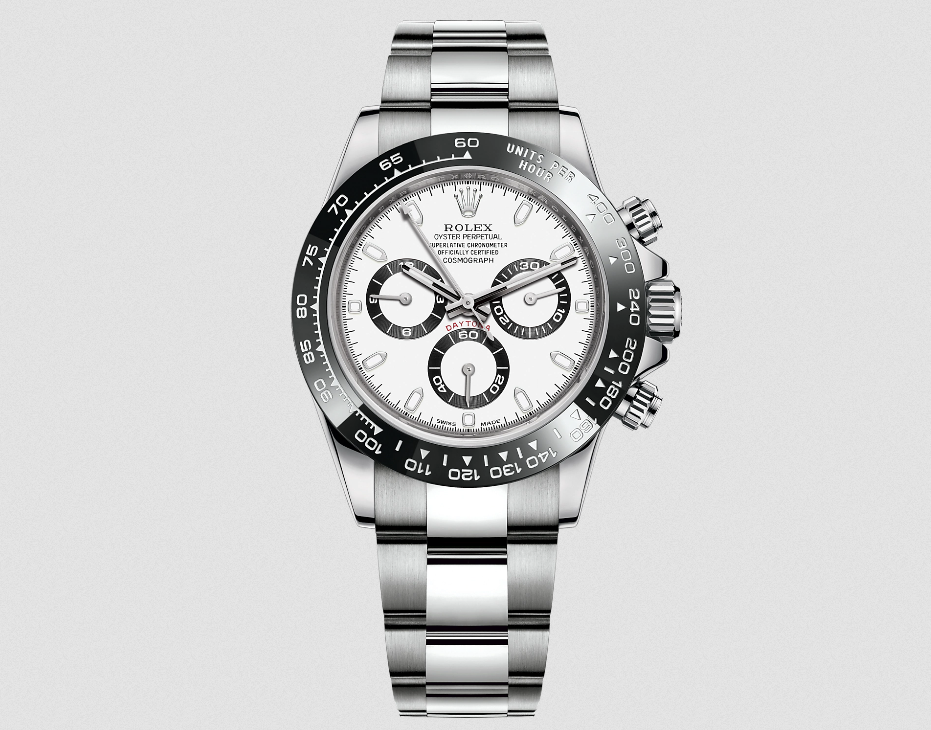

Take for example, a modern Rolex Daytona. At any authorized dealer, the item is not available for purchase to just about anyone (unless the client has a substantial purchase history). It would appear that supply is drastically short of demand. However, on the grey market, there is absolutely no lack of availability. Pay the 2X or 3X markup over MSRP and a potential buyer can have their choice of nearly any model they want, ready for purchase, shipped worldwide, usually overnight or within a few days at the latest. Once bought however , the social status associated with owning the piece is either linked to the fact that the person had the money to pay market price or had the purchase history to get one at retail. Either way, the watch represents roughly the same amount of “background wealth” when seen on the wrist of the owner.

This appears to be the key link between the perfect and imperfect markets. If a consumer wants to purchase an item in either market condition, all other things being equal, the governing forces will dictate that the cost is the same, no matter where (grey market vs authorized retail market) the item is purchased. Want to get a 116500LN from a retailer? Go to an authorized dealer and you can expect that in addition to your purchase of the this panda-dial steel Daytona, you’ll have to purchase enough other “regular goods” (for which the MSRP is more than the second-hand market price) where the resale value of these goods will roughly equal the markup over MSRP that you’ll have to pay on the grey market for that hot watch you wanted in the first place.

In equation form:

(Grey Market Value of watch X) — (MSRP of watch X) = resale value of bundled goods purchased to be eligible to buy watch X at MSRP

Clarification note:

Resale value = what you can sell a product for after you’ve bought it.

Retail value = what you pay for a product at an authorized dealer (MSRP)

How will Manufacturers respond:

If you go to a vendor where, of the things they sell, most of the items command higher second hand prices than retail (think of AP, Rolex and FPJ boutiques), then expect the shelves to be nearly, if not completely empty. They simply do not have goods that should stay un-sold. That is to say, the factors that made their products desirable in the first place led to a successful campaign where all their products actually sold out. Unlike a jewelry store or multi-brand vendor where there are other products worth less than MSRP, all the items for sale at a specialty, one-brand boutique (such as Rolex, AP, or PP) are already spoken for (because they’re worth more on the grey market than what you’d pay at the boutique). They do not have any other items that they can bundle or sell to a customer to make up the unrealized gain that they will lose out on when they sell their items at MSRP… and eventually, it becomes available for more on the second-hand market. So naturally, what happens? The vendor soon increases their retail prices to more closely reflect the grey market prices because they have no other way to capitalize on the potential profit margin that the market would otherwise allow them. These are businesses, after all, and do not always enjoy fixed labor or material costs on the manufacturing end. Add to this the current economy where skilled workers are at a premium, and it becomes clear that manufacturers face their own pressures despite enjoying a booming watch market (example: FP Journe).

If the brand has the luxury of not increasing their retail prices (think PP who, in part, proposes to look past short-term economic cycles and has the financial capital to work the long game), then they can focus on an alternate strategy. They can demand long-term brand loyalty from customers and start black-listing flippers. Despite having wholesalers and retailers as middle men, Patek can essentially “contract” with their customers. For their part, PP agrees to not drastically raise MSRP to reflect grey market prices and can, in turn, expect customers to not sell the pieces for profit as part of this contract. The customer then gets the “privilege” of being “allowed” to buy more pieces from them in the future. Patek, also as part of their “contract”, works on protecting brand value/image, maintaining exclusivity, and driving secondary market prices in any number of ways (marketing, making unique pieces, providing publications reflecting a lifestyle, employing super-specialized artisans, maintaining a museum to publicly display the desirability of their products, bidding at auctions, supplying Only Watch for DMD with over-the-top pieces, and doing things to “generate hype”) so that a Patek owner can continue to rely on building value in the pieces they own — possibly even for generational wealth.

AP’s ADs free to set resale prices:

Closing thoughts:

Ultimately, many of the conversations we’re having as part of the horological zeitgeist are facets of the same underlying economic principles. Did you see what the Tiffany 5711 pulled at auction? Can you believe that AP is allowing their ADs to set whatever (retail) price they want? I wonder how much FPJ will raise their prices? Did you get that [hot watch] at retail? Are you the original owner of that Aquanaut? Consider whatever the answers you might expect to hear to these questions that are making their rounds through our communities (on line, through social media, and in person). I believe that for the most part, we’re all looking at different aspects of the same winds of change running through our hobby. And as for that firmly held, focal belief that we often see people hanging on to: “I won’t pay anything more than retail,” I urge a little reflection on the bigger picture.

Image sources & references:

- www.rolex.com

- www.audemarspiguet.com

- www.blogspot.com

- www.investopedia.com

- https://www.amzlogy.com/amazon-seller-glossary/what-is-msrp-manufacturers-suggested-retail-price/

Vinay

Very well written and logical essay.